The Nickersons

In the wake of Rodney Nickerson's death in Alta Dena during the Eaton Canyon fire.

The following post is from my drafts. I wrote it back in December, shortly after TDE hosted their annual Christmas concert and toy drive in Watts. It was imagined as a component of an ongoing series about the GNX album and the feelings it conjured up in me. This one was inspired by “Wacced Out Murals” which, for no reason at all, plays on a loop in my head. Especially this part:

“This is not for lyricists, I swear it’s not the sentiments/Fuck a double entendre, I want yall to feel this shit/Old soul, bitch, I probably built them pyramids/ducking strays when I rap battled in the Nickersons/Where you from? Not where I’m from, we all Indigenous” -“Wacced Out Murals,” Kendrick Lamar

I think it’s because of the cadence in this portion of the song, but it inspired me to write what follows— a random post about the hallowed ground of the Nickerson Gardens Housing Projects in Watts, CA. After seeing the viral news story on social media about Rodney Nickerson dying in his bed in his Alta Dena home after refusing to evacuate, I thought to share it.

Nickerson, 82, was the grandson of William Nickerson, the founder and owner of the Nickerson Garden Housing Project in Watts, where my family lived when they were transitioning from Mississippi to California.

For the past few days, Los Angeles city and county have been battling devastating fires compounded by a wind event that has exacerbated the destruction. The Palisades Fire has received the lion’s share of media attention, and for good reason— it will go down in history as the fire that caused the most structural damage in Los Angeles history. It also impacted an iconic wealthy neighborhood on the shore of California where many celebrities live(d). However, the equally devastating Eaton Canyon Fire that ravaged Alta Dena is worthy of attention as well, albeit for different reasons. It’s desecrated one of the oldest historically Black working-class neighborhoods in the L.A. area.

I’ve just been sitting here thinking about this man dying in his home and what his thought process might have been when it came to not evacuating. This was a home he bought in 1968, and in it, he bore witness to countless natural disasters and upset in the city— the uprising in 1992, the Eaton Canyon fire of 1993, the earthquakes in 1971 and 1994, as well as countless other quakes, wildfires, El Ninos, and Santa Ana wind threats. I don’t know this man, but I can hear him saying, as his daughter Kimiko reports “If I need to go I’ll go, but I don’t need to go right now” and “I’ll be here tomorrow.” It’s haunting. I know there are folks who will rush to pathologize him for being stubborn or ignorant, but I think his words and his tragic death speak to the depths of denial about what’s happening in Los Angeles that we’re all experiencing.

If you're not from California or have not lived there for a significant amount of time, you may not understand how unprecedented these fires are. I lived in Los Angeles most of my life and have never seen a fire cause so much structural damage to the people who live in the city. Most often, wildfires happen “out there,” not “over here.” Meaning, that they happen in areas that are unfamiliar to most L.A. residents-- out on the outskirts of the city or county where there's a lot of dry brush and forest area. Usually, these fires do not take things that are familiar to the city folks. This fire feels different because there are so many happening at once and also because it's consuming the familiar.

*deep sigh*

Again, what follows is about Nickerson Gardens, and was written a while back and unrelated to the fires. It’s more a snapshot of L.A. history and the significance of Black Spaces in Los Angeles but I hope you enjoy it as we all continue to reckon with what is lost when buildings go.

I know I’ve made being from Los Angeles my entire personality, and this can be really annoying for some people but I think it’s extremely important to note that I’m aware, and I really don’t care how anyone else feels about it. I love my hometown and am unapologetically enthusiastic about the things I love. I feel like one of God’s biggest blessings over my life was my grandmother deciding that she could not handle the cold in Detroit and needed to move back to Mississippi. Unlike her sister Kate, who stuck it out and lived in Detroit for the rest of her life with her children (my aunts and uncles), my granny Mae was free to try out a new city. That freedom and willingness to start over brought her to Compton, CA, in 1963 and shortly thereafter to Watts, California, and its Nickerson Gardens Housing Projects by 1964. This simple decision meant that a couple of decades later, I got to grow up between South Central Los Angeles and Inglewood, CA. Honorable mention to my daddy for figuring out how to make it out west from Waycross, GA (a story for another day).

“The Nickersons,” as they’re colloquially called, is the largest housing project ever built in Los Angeles, CA. Despite what anyone might try to say about its reputation today, it’s important to acknowledge that The Nickersons are hallowed ground as far as I and many other Black Angelenos are concerned.

The Nickersons were built as transitional public housing by the Texas-born Black businessman William Nickerson and designed by the renowned Black architect Paul R. Williams. The housing project officially opened in March 1954 as an experimental solution to the “problem” of insufficient housing for the influx of Black folks to L.A. from the south during the second wave of the Great Migration (1940-1970). The housing crisis was contrived of course— many L.A. neighborhoods had housing covenants that restricted black people from renting or buying in the area. William Nickerson envisioned his housing project as an easy place for Black folks to live while figuring things out.

The names affiliated with the housing project-- William Nickerson and Paul R. Williams-- signified the promise of life in Los Angeles for migrants from the South-- it was rumored that opportunities beyond the restrictions of the Jim Crow segregated South were abundant there. William Nickerson, the namesake for the housing project, was a prominent businessman himself and a testament to this. He owned and operated Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company -- the largest black-owned insurance company west of the Mississippi and the first in the city to offer insurance to all people, regardless of race. At the time, many insurance companies across the country either did not sell policies to Black people or, if offered, did not honor them in instances of need.

Nickerson started Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company with some of his business friends after relocating to Los Angeles. The Prairie View alum from the Coldspring, Texas area, came because his early success as a cofounder of the American Mutual Benefit Association (AMBA) put him on the radar of the local white power structure. AMBA made a small fortune selling insurance policies to Black Americans when other insurance companies refused. And although white folks were unwilling to sell to Black folks, they didn’t like the idea of Black folks setting up their own businesses either. They certainly didn’t like Nickerson using his money to start other business enterprises like the Houston newspaper he established (the Houston Observer) and the publishing house (Informer Publishing Company). Local Klan members communicated their disdain with a burning cross planted in his front yard, and Nickerson took that as good a sign as any to pack up his belongings and move out west to the seemingly more liberal California.

The second name associated with “The Nickersons” is Paul R Williams, the first certified Black architect west of the Mississippi. Unlike Nickerson, Williams happened to be born in Los Angeles, but he also shared a migrant history, as the rest of his family had come to L.A. from Memphis right before his birth in 1894. They came to start a fruit business but it failed. Later, both of his parents passed away of illness. Despite ending up in foster care, Williams was eventually adopted and went on to study architectural engineering at USC, graduating in 1919. He would go on to have a remarkable career in which he became known as “Hollywood’s Architect,” building homes and other structures for many stars, including Frank Sinatra, Desi Arnaz, Lucille Ball, Cary Grant and many others. I think he might be perhaps best known for designing the LAX Theme Building -- the “futuristic” looking structure in the middle of LAX airport. His career flourished despite many people telling him that no one would hire him because he was Black and that there was not enough rich Black clientele to support his career. They were wrong.

Again, for Black folks newly arrived to Los Angeles in the 50s and 60s, these two men signified what was possible “out west.” Their names welcomed generations of folks who just wanted to make a decent living without dealing with the burden of racism pulling at the threads of everything they cobbled together.

Like Nickerson, my great-grandfather, affectionately known as “Daddy Carr,” had moved to Los Angeles from Mississippi for similar reasons. As a skilled blacksmith and small business owner, his poor white neighbors didn’t take too kindly to his success, but Daddy Carr didn’t wait for the cross to appear in his yard. He sensed the changing tide after a white neighbor came over to hire his daughters (Granny Mae and Aunt Kate). As I’m told, the neighbor didn’t like Daddy Carr’s response, “My girls don’t work.” Daddy Carr took that hostile exchange as his sign that it was time to go. He had an offer in hand to move out west to work on one of the ranches in the San Fernando Valley, out near Los Angeles anyway. Apparently, some white guys needed some good “cowboys” to train and tend to the horses that were used in film and television productions.

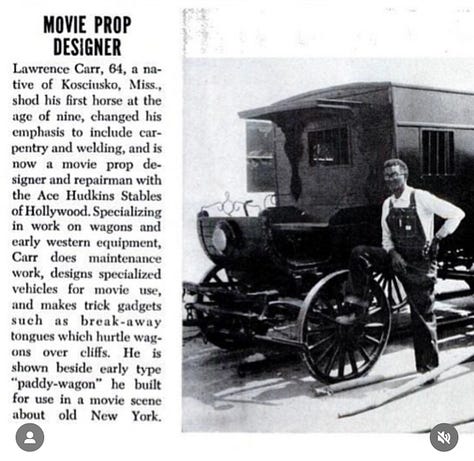

Like Paul Revere Williams, Daddy Carr was highly skilled. He may not have had an engineering degree from USC, but his skills as a blacksmith warranted him not only a job on a ranch servicing the movie studios but also an appearance on a television show (I so wish I could remember the name right now). He also got a short write-up in Ebony Magazine about the prop cars he designed for movie sets, that could “crash” on demand and like a transformer, reassemble after a string was pulled.

At the time, Compton, CA, was an affluent area in Los Angeles. Former President H.W. Bush, his son George W. Bush, and former first lady Barbara Bush, once called Compton home (in 1949). It was situated south of downtown L.A., and near Central Avenue-- a long pathway spanning from DTLA (downtown) to Compton. The street became the epicenter of Black life in Los Angeles.

Central Avenue was where many of the Black businesses were located. The Hotel Somerville (later The Dunbar Hotel) for instance, was built explicitly to house attendees of the 1928 west coast convention for the NAACP by Dr. John Alexander Somerville (USC alumni may recognize the name). It was erected at a time when no other hotels in Los Angeles would house Black people and was ultimately frequented by every Black celebrity of the day who visited L.A. (i.e. Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, Billie Holiday, etc.). It was also once known as “Little Harlem” because it was the west coast center for Black culture and life, especially Jazz music in the 1940s and 50s. It was home to the Central Avenue Jazz Festival and the Cavalcade of Jazz-- the largest outdoor jazz entertainment event at the time which was held at the long gone Wrigley Field. Nickerson’s Golden State Mutual Life building’s original headquarters were on Central and the 27th Street Bakery was not too far away. Most people today won’t recognize the name, but they will know their infamous sweet potato pies, which are sold all over Los Angeles at places like Ralphs and Louisiana Fried Chicken. And of course, Nickerson Gardens, was erected on Central in Watts.

Daddy Carr and Mama Carr stayed all the way down off the southern end of Central in Compton because the neighborhood was zoned for farmland (and still is to this day!). So they could keep their animals with no issue. The Nickersons were not far away.

Like any small child, my mother marks the time of her relocation from West Point, Mississippi, to Compton, CA, years later by the punctuation marks of certain earth-shattering life events that stood out in her young brain-- Mama Carr’s seemingly terminal illness, which brought Mae (her mother, my grandmother) and Kate to her bedside in Compton, California; and the following summer when Mae sent for her and her 8 siblings. She also clearly remembers a few months into the move, when President JFK was assassinated.

1963 was undoubtedly just the beginning of an extremely tumultuous decade in the lives of every American, but for Black Americans in general and my family specifically, it was a mixed bag-- things got worse, but at the same time, things were also getting a lot better. Please don’t get me wrong, conditions for Black Americans were mostly deplorable, and racism and poverty were ravaging Black communities, but folks had hope that things were changing and that meant something.

At some point, my granny had to find somewhere for her family of 11 to live. They couldn’t stay in Mama Carr’s home in Compton forever. While she scrounged up enough money for the down payment on a house, they temporarily moved to The Nickersons in nearby Watts. My mother barely remembers her time there, but says it was mostly good. The worst part being the uprising in 1965 because she had never experienced anything like it.

My grandmother was actually standing out on the street when the traffic incident that sparked the uprising occurred. I can’t tell how much of her eyewitness account is what actually happened or the rumors that were circulating on the street that day but the entire incident was a reminder that things in L.A. weren’t always so sweet.

Like the housing projects that were developed in major cities all over the country to accommodate migrating Black families, the projects worked for many at one point but ultimately created some unforeseen consequences. As an article from the Paul R Williams Project explains:

“The original intent of both Williams and the Housing Authority in designing and building Nickerson Gardens was to provide low cost, safe, transitional housing… Fifty-years later, it was generally agreed that concentrating so many poor people in a limited area creates a self-contained, isolated ghetto.”

My family was fortunate enough to reside in the Nickersons in some of its best years. For them, the Nickersons lived up to its promise. They were happy to make a home at 1221 E. Imperial (Unit 217) and the 1,065 other units that constituted the 156 buildings on the sprawling 69.6 acre complex provided the same for hundreds of thousands of Black people— their neighbors, those who came before them and after them. Many of whom, in those first decades at least, were brand new to Los Angeles.

My family didn’t live there long, but they were there long enough for my mom to attend 112th Street elementary for a year and complete a semester at Gompers. By the second half of the 7th grade she was enrolled at Horace Mann Middle School which was closer to the home my granny and grandfather purchased on Cimarron Street. When they moved in, they were the first Black family to live on the 8600 block of Cimarron off of Manchester Blvd. (the 5900 block would later be immortalized on film as the neighborhood of Tre, Ricky, Doughboy, and Brandi in the 1991 film Boyz N the Hood).

While writing this, I took a break to call my mom for fact-checking purposes. During our conversation, I asked her if she ever ate at Hawkins Burgers and she asked me how I knew what Hawkins burgers was. I grew up on the west side so the east side is like a taboo for us. Although my mother worked in Watts at King hospital for decades (you may remember it as the hospital Caine went to after he was shot in Menace II Society, 1993) she didn’t do anything else on that side of town and while growing up, I was told in no uncertain terms that I had no business being over there.

She confirmed that she had gone to the original Hawkins Burgers, way back when, before eminent domain demolished all of the houses behind it to construct the 105 Freeway. My mother said she knew the Hawkins family, who had been in the area since the 1930s. Everyone in the neighborhood did. She told me they used to own a funeral home and a few other businesses. She said that the current house isn’t the original structure. A lot had changed in the Nickersons since she lived there in 1964-65.

She described the Nickerson’s to me-- the courtyard in the center, the way the clothes lines were erected behind all of the units. I told her “They’re still there.” “How do you know?” she asked. So I showed her Khalil Joseph’s short film “Until the Quiet Comes,” a visual component to electronic music producer Flying Lotus’ album of the same name. It’s set in Nickerson Gardens.

Via FaceTime, I watched her watch the video in silence. She didn’t really have too many comments afterwards. I also didn’t press her about it. She only lived there briefly and even though she worked around the corner at King Hospital for decades, she never really returned to the Nickersons after the day the family moved out in 1965 just a few short months after the Watts Uprising rocked the city. Considering the fact that she hasn’t been back physically, I’m sure she’s not super interested in going back mentally either. So I let it be but if that complex could talk, the stories I think it would tell.

Thank you to the Nickerson Family. Your family has touched the lives of so many other Black families in Los Angeles and we are mourning this tragedy right alongside you.

With love,

-Brooklyne.

I’ve been thinking about different kinds of gardens recently and this post recontextualized Nickerson Gardens as a garden that cultivates and grows people 🌱 Thank you for sharing this history of the land and your family!